PARCHMAN, Miss. (AP) — The longest-serving man on Mississippi’s death row was executed Wednesday, nearly five decades after he kidnapped and killed a bank loan officer’s wife in a violent ransom scheme.

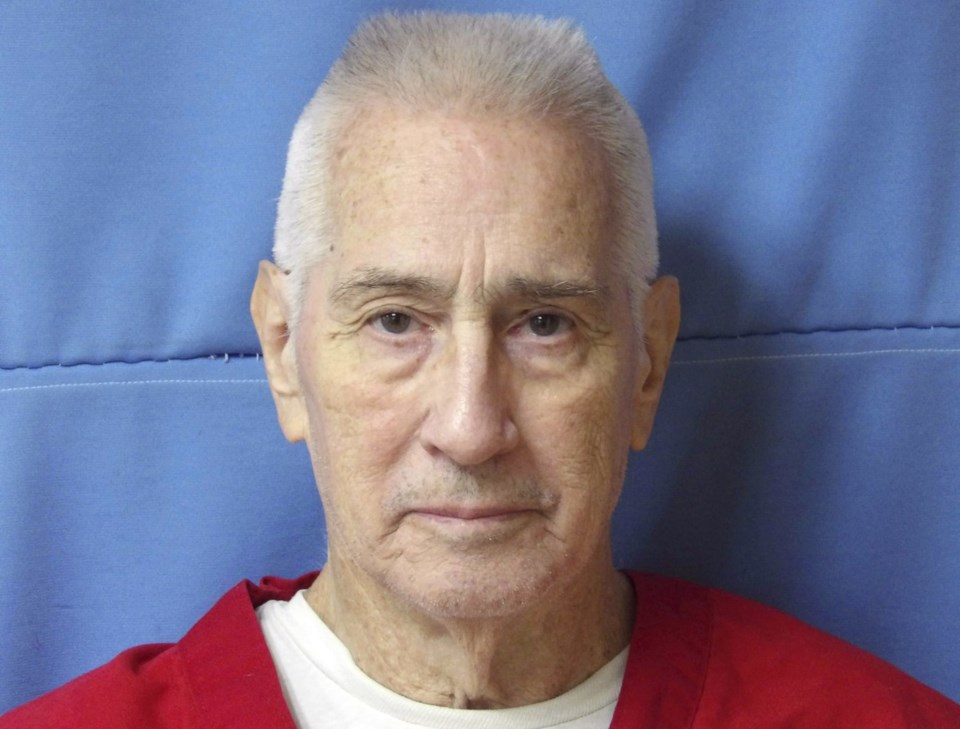

Richard Gerald Jordan, a 79-year-old Vietnam veteran with post-traumatic stress disorder whose final appeals were denied without comment by the U.S. Supreme Court, was sentenced to death in 1976 for killing and kidnapping Edwina Marter. He died by lethal injection at the Mississippi State Penitentiary in Parchman.

The execution began at 6 p.m., according to prison officials. Jordan lay on the gurney with his mouth slightly ajar and took several deep breaths before becoming still. The time of death was given as 6:16 p.m.

Jordan was one of several on the state’s death row who sued the state over its three-drug execution protocol, claiming it is inhumane.

When given an opportunity to make a final statement Wednesday, he said, “First I would like to thank everyone for a humane way of doing this. I want to apologize to the victim’s family.”

He also thanked his lawyers and his wife and asked for forgiveness. His last words were: “I will see you on the other side, all of you.”

Jordan’s wife, Marsha Jordan, witnessed the execution, along with his lawyer Krissy Nobile and a spiritual adviser, the Rev. Tim Murphy. His wife and lawyer dabbed their eyes several times.

Jordan's execution was the third in the state in the last 10 years; previously the most recent one was carried out in December 2022.

It came a day after a man was put to death in Florida, in what is shaping up to be a year with the most executions since 2015.

Mississippi Supreme Court records show that in January 1976, Jordan called the Gulf National Bank in Gulfport and asked to speak with a loan officer. After he was told that Charles Marter could speak to him, he hung up. He then looked up the Marters’ home address in a telephone book and kidnapped Edwina Marter.

According to court records, Jordan took her to a forest and fatally shot her before calling her husband, claiming she was safe and demanding $25,000.

Edwina Marter’s husband and two sons had not planned to attend the execution. Eric Marter, who was 11 when his mother was killed, said beforehand that other family members would attend.

“It should have happened a long time ago,” Eric Marter told The Associated Press before the execution. “I’m not really interested in giving him the benefit of the doubt.”

“He needs to be punished,” Marter said.

As of the beginning of the year, Jordan was one of 22 people sentenced in the 1970s who were still on death row, according to the Death Penalty Information Center.

His execution ended a decades-long court process that included four trials and numerous appeals. On Monday the Supreme Court rejected a petition that argued he was denied due process rights.

“He was never given what for a long time the law has entitled him to, which is a mental health professional that is independent of the prosecution and can assist his defense,” said lawyer Krissy Nobile, director of Mississippi’s Office of Capital Post-Conviction Counsel, who represented Jordan. “Because of that his jury never got to hear about his Vietnam experiences.”

A recent petition asking Gov. Tate Reeves for clemency echoed Nobile’s claim. It said Jordan suffered severe PTSD after serving three back-to-back tours, which could have been a factor in his crime.

“His war service, his war trauma, was considered not relevant in his murder trial,” said Franklin Rosenblatt, president of the National Institute of Military Justice, who wrote the petition on Jordan’s behalf. “We just know so much more than we did 10 years ago, and certainly during Vietnam, about the effect of war trauma on the brain and how that affects ongoing behaviors.”

Marter said he does not buy that argument: “I know what he did. He wanted money, and he couldn’t take her with him. And he — so he did what he did.”

Sophie Bates, The Associated Press