Deep into January, some portions of Manitoba’s winter road systems are opening up. When I checked the Manitoba Highways website before typing up this piece Jan. 27, there were a bunch of them open – with weight limits in effect, granted.

Now, dozens of small places, including several Indigenous communities, are tied to the rest of the province. People in Tadoule Lake can actually drive in and out of town now. People in Lac Brochet or Oxford House or Poplar River can access the outside world on the ground. That’s good news for each of these towns, but there’s always one question I think of when the winter road season opens – why aren’t these communities connected by actual year-round roads?

So many locations in the north are completely cut off from the rest of Manitoba (and Canada) by land transport for much of the year. Churchill was completely cut off for months after the rail line went out.

If we are serious about looking north and helping out the economy of northern communities, we should make transport from community to community as easy as possible. The best solution I can think of is to build permanent, all-weather roads across the province.

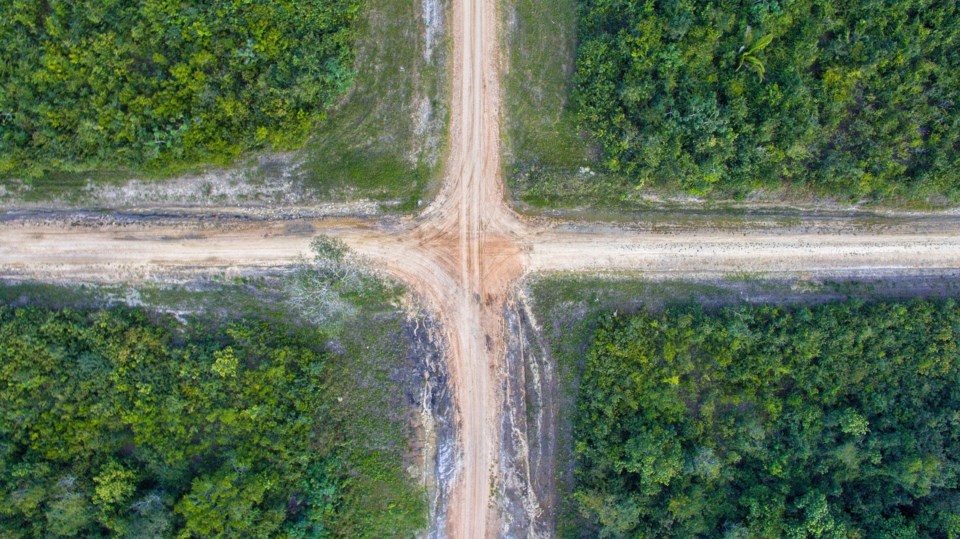

I’m not asking for a twinned highway stretching all the way to Arviat or Rankin Inlet – while that would be great, I will concede that won’t work. Standard two-lane blacktop going up to O-Pipon-Na-Piwin Cree Nation might be too much to ask, too. That said, is cutting down some trees, levelling out some land and laying down a strip of gravel too much to ask?

The provincial government currently operates about 2,400 kilometres of winter roads each year. Back in 2014, building and maintaining those roads costs about $8.2 million.

Those roads were open for trucking for about six weeks.

I know that the immediate cost would be the number one concern of anybody arguing the opposite of this view. Building roads to these towns would be expensive. It would be time-consuming. The odds are high that finding qualified labour wouldn’t be easy.

All that said, is it impossible? I doubt it.

In doing research to determine how much it would cost to build gravel roads to remote communities in Manitoba, I found very few ways to estimate a price. I stumbled across a report from the World Bank about a project to build roads in the African nation of Lesotho, which is located in the rural portion of South Africa, far away from major population centres. The country is dirt poor. Guess what the per capita GDP in Lesotho was last year. According to the International Monetary Fund, it was $1,338 per person per year. Canada’s nominal per capita GDP is 35 times higher.

That said, back in the ‘80s (when it was even poorer, mind you), Lesotho completed a highway project including regravelling, rebuilding and upgrading more than 500 kilometres of roads.

The overall cost of that project? A one-time payment of $15.2 million US, covered mostly by international development agencies and funds, including the Canadian International Development Agency.

Keep in mind, that’s in a fairly remote, impoverished country, almost 40 years ago. Despite their circumstances, Lesotho found a way to pay for and build needed roads. What’s Canada’s excuse?

Think of the economic and personal gain places like Shamattawa or Pukatawagan could experience if you could transport goods there by road. We’ve all heard stories about or seen photos showing how expensive food or basic household supplies cost in these communities. Flying goods into a community isn’t cheap, nor is it efficient. Do we really care about a northern community if we’re seemingly okay with its residents paying $14 for a bottle of ketchup or $65 for a ham? Think of the business opportunities in shipping and travel. Think of how local entrepreneurs, the people the provincial government has pretended to care so much about, could take advantage.

It’s never going to be as cheap to live in the north as it is in the south or in a city, but the cost shouldn’t be exorbitant.

The other easy answer against this is saying people living in remote northern communities should move away, somewhere where the standard of living may be higher, where there may be opportunities not available at home.

First off, we should not have to expect people to move away from lands they have ancestral or personal ties to just to live. No northern community would thrive, or even survive, if everybody just up and left one day – including Flin Flon.

Second, even if we grant that proposition, how exactly does somebody move away from a northern community? There’s no damn road! The person wanting to leave would have to pony up money for a plane ticket – which, as we all know, are exorbitantly expensive in the north and always have been – or find an alternative way which may be dangerous.

By that same token, how exactly would somebody move to a northern community without a road? If you’ve gone away, got your degree or trade certificate or whatever and you want to move back home to help out, it’s not like you can just hire a U-Haul in the summer and drive it to Red Sucker Lake.

I’m not going to pretend that I know what’s best for every community not currently hooked up to the provincial highway system year-round. I may be a bit bullheaded, but I’m not stupid. I’m merely suggesting that constructing all-weather roads in the north could create equitable opportunities for people here, chances that people may not have had available before.

If we want to help remote communities find some kind of economic prosperity, wouldn’t it be best to provide for one of the most basic freedoms a person can have – freedom to move?