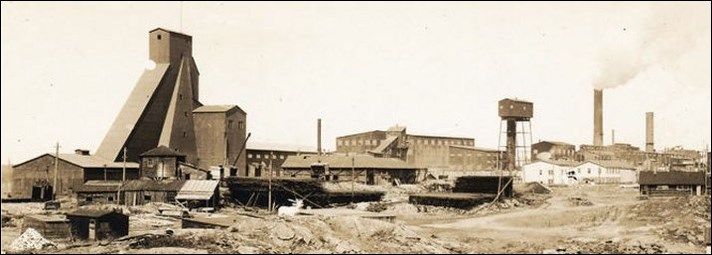

Living uptown, especially on Church Street, we were essentially on the doorstep of the mine operation that ran 24/7, 365. We grew accustomed to the ever-present rumble, clang and bang that emanated from the mill and smelter. One aspect I especially recall from my 1940s-50s days was the sounds of whistles and sirens. The whistles were, of course, timed to give shift change direction to the surface workers. The whistles also provided timely reminders to the townsfolk – and to the children.

My “intensive research” (emailing Flin Flonners of that era) brought forward a variety of recollections about the timing and intent of the sirens and whistles. Basically, and by consensus, there were two whistles at the plant. The main and loudest whistle could be heard all over town and sounded the important times. The second whistle of a lower tone and volume sounded at 12:30 p.m. and 4:30 p.m. The siren was reserved for fire emergencies, blast warnings and curfews. I don’t know the location of the whistles but believe the siren was or is located on top of the company water tower.

One recollection indicated the main whistle sequence in this manner: 8 a.m. whistle or siren (Dad - go to work), 12 noon whistle (Dad home for lunch), 1 p.m. whistle (Dad back to work), 5 p.m. whistle (Dad home for supper). Note: Only the “main office” staff who lived near the mine site were able to scoot home at noon. The rest of the surface workers were ‘lunch-pailers’.

The siren, of course, was sounded in several cycles to alert members of the Flin Flon Fire Department – this being pre-portable telephone days. The telephone operator would receive the fire call, sound the siren and then make a series of calls to the firefighters who would head to the fire hall or the scene of the fire. There was also a special fire phone in the CFAR control room where the announcer would get the location of the fire and broadcast this as another source for the firefighters who were not near a phone. The difficulty was that the radios of the day were “tube-type” and would take a moment or two to “warm up”, thus requiring the announcer to repeat the location. As the locals considered it “good fun” to jump in the car and head for the fire, the announcer would also warn residents not to impede the fire trucks.

My sources (and I) were somewhat confused about the timing of the curfew siren (9 p.m.-10 p.m.?) that signalled the youth (15 and under?) to get home. My recollection is that the curfew was in effect in the late 40’s/early 50’s period.

Going back to the first days of open pit blasting, there was a loss of life of a young lad on Creighton Street (and plenty of damaged roofs) as the result of rock debris falling from the massive dynamite explosions at the pit site. Thus, Hudson Bay Mining and Smelting established a procedure to warn uptown residents of impending blasts. This evolved into a standard procedure well into the 1950s even when the blasting occurred a few thousand feet underground. On the day of the blast, a hand-delivered notice would announce that a “take shelter” warning siren would sound at 4:50 p.m. The explosion would occur at precisely 5 p.m. Our little house on-the-side-of-the-rock on Church Street would shake and the dishes would rattle a bit as the vibration travelled through the rock. The “all clear” siren would follow.

In a related anecdote from Brian Kenny: “Our family fondly remembers my aunt Joyce Bongfeldt who married my uncle Chester. She came to Canada as a war bride and they stayed with my parents for a short time. The war was just over (1945) and aunt Joyce had been an ambulance driver in England during the war. The German Luftwaffe blitz bombed England, thus she was thus quite familiar with air raid sirens and the survival drill. One day the ‘take cover’ blasting siren went off and aunt Joyce thought it was an air raid. She grabbed me and my baby sister Sharon and we all dove under the bed.”

Folks, we can’t remember everything with absolute accuracy, so… if anyone has any whistle-blower amendments or additions, please toot off and email to the address below.

Thanks to Bob Putko, Ron Dodds, Linda Allen, Stu Bexton, Brian Kenny, Maxine and Garnett Wheeler and Ron Wiebe for their input.