As Eric Westhaver and his classmates posed for a group photo, a Flin Flon landmark loomed large in the background – but something was different.

It was early June of 2010 and the HBM&S copper smelter had just closed, meaning its towering smoke stack was no longer emitting clouds of toxins.

The development tied in with discussions about global industry Westhaver and his classmates were having in their geography class at Hapnot Collegiate.

“We got a picture of the whole class with the stack in the background with no smoke coming out of it,” he recalls. “It seemed really novel to us because we had never seen it like that before.”

Westhaver, who came of age in Flin Flon beginning in the late 2000s, could recall smelter smoke so thick he couldn’t see to the end of Green Street near his home. As a child, that scared him.

When the smoke was gone for good, he experienced mixed feelings.

“There was definitely an awareness of what [the smelter did] for Flin Flon and what Flin Flon stood to lose by having the smelter close,” Westhaver says. “But you had to weigh the pros and cons, the con being a lot of positions were eliminated…but on the positive side, you could walk out of your house in the summer and not feel like you were choking.”

Smelter smoke aside, Westhaver, now 23 and working as a reporter for The Reminder, recalls his Flin Flon upbringing with fondness.

“I can remember Lloydy’s Corner Store opening up [in 2007], and that was a big youth hangout for a while,” he says.

“They hired a lot of neighbourhood kids in the summertime. You would be able to see a lot of people from class working the till or stocking shelves. They did a lot for neighbourhood youth at that point.”

Outside of work and class, youth would socialize at bush parties – “there were a few places here and there,” Westhaver notes – or get together at the home of a buddy whose parents were away for the weekend.

“That was what the nightlife was for

Flin Flon adolescents at that point, but I kind of shied away from that a little bit,” says Westhaver.

While partying wasn’t his thing, sports were. Westhaver was a big fan of hockey, playing the sport himself and regularly watching the Bombers play at the Whitney Forum.

“Our age group was probably one of the first where hockey was not a major thing because, historically speaking, that was always a sport that a lot of people here cared about and took part in,” he says. “I can remember my graduating class from Hapnot, there were maybe two or three people who played hockey. I felt like I was the weird one for playing.”

Westhaver says the declining interest in hockey may have been the result of youth participating in more affordable sports such as soccer and baseball.

Affordability was particularly important to parents during the Great Recession, which began in 2008.

This region felt the recession’s impact when HBM&S closed its Snow Lake operations for most of 2009. Several dozen contractors were put out of work, while nine Flin Flon-based HBM&S employees were laid off as Snow Lake-based workers bumped into their positions.

Westhaver, who spent the first two years of his life in Snow Lake, remembers the state of affairs that year.

“There were a few families who moved to Flin Flon full-time after that who have stayed,” he says. “There were a couple of cases where someone would move to Flin Flon and share a place with a few other friends or relatives of theirs, work and then head back to Snow Lake on the weekend, or save up money to move their family.

“My dad did kind of a similar thing around the time I was born, where he was working in Flin Flon but our family was still living in Snow Lake. I think it’s kind of interesting how there’s been a change where in the past you had people living in Snow Lake and commuting to Flin Flon and now you have people living in Flin Flon who are commuting to Snow Lake.”

Westhaver’s first steady job was as a DJ and announcer at CFAR. He had the rare opportunity to work in professional broadcasting from the time he was 15.

“It was really unique,” he says of the experience. “It gave me kind of a weird spot in the social fabric of my age group in Flin Flon, because nobody else did that kind of thing.”

Westhaver never felt like a celebrity, noting that if his chest got too puffed up from a good broadcast, he would soon be humbled by the realization he was just another teenager with math homework due the next day.

Not surprisingly, Westhaver followed the news as a teenager, including the five-year debate over nuclear waste storage in Creighton.

Nuclear Waste Management Organization (NWMO) was considering Creighton for an underground storage facility for Canada’s used (but still radioactive) nuclear fuel rods.

Westhaver respected the opposition to the NWMO proposal but also believed the project did not represent a major risk.

“I can understand hearing, ‘Radiation is going to be stored near your town’ and hearing people flipping out and thinking, ‘That’s dangerous,’ thinking of Chernobyl and thinking of all these horrible things,” he says. “But at the same time, the way it had been discussed did not seem all that dangerous. It seemed experimental in some ways, but it didn’t seem like it was going to be a slow, horrible death of the region.”

In 2015, NWMO removed Creighton from consideration not because of public opposition, but because of unsuitable geology.

By then, Westhaver was three years removed from high school and studying journalism at the University of Regina. After graduating in 2016, he was hired as a reporter at The Reminder.

Soil study

In 2007, Manitoba Conservation released a study showing elevated metal concentrations in much of Flin Flon’s soil.

Researchers would spend the next six years trying to determine whether industrial-borne metals in the environment posed a risk to human health.

HBM&S, now part of Hudbay, commissioned the independent firm Intrinsik Environmental Sciences to study the matter.

Elliot Sigal, a scientist who worked on the project, summed up Intrinsik’s conclusion in 2013: “You can never say there’s zero risk, but it’s essentially zero.”

This reassuring finding was based on a study that saw dozens of Flin Flon children provide blood samples in 2009 and 2012.

The 2009 results showed that while lead levels in children did not exceed formal health guidelines, 15 per cent of participants had levels viewed as “elevated” based on the precautionary baseline used in the study.

Follow-up tests in 2012 showed a dramatic decline of lead levels across geographical, age and gender categories. On the whole, blood lead levels were about half of what they were in 2009.

The decline followed industrial and community efforts to limit lead exposure, but Sigal said the biggest development was the June 2010 closure of the HBM&S copper smelter, which had been Canada’s single largest emitter of the metal.

Sigal said the 2012 blood lead levels were, on average, “marginally higher” than those found in non-industrial communities, but well below health guidelines.

He said the blood lead levels fell below the level at which the US Centre for Disease Control recommends action to limit exposure, “so I think we can take some assurances in that.”

While the study involved data from the era of the copper smelter, it did not speak to potential health risks that existed in previous years and decades when the pollution was more severe.

Investing in the future

Massive investment in the Flin Flon region’s mining and business sectors highlighted this decade.

While Hudbay closed its antiquated copper smelter in 2010, this necessitated the addition of a filtration plant to make unsmelted copper concentrate lighter and thus more economical to sell.

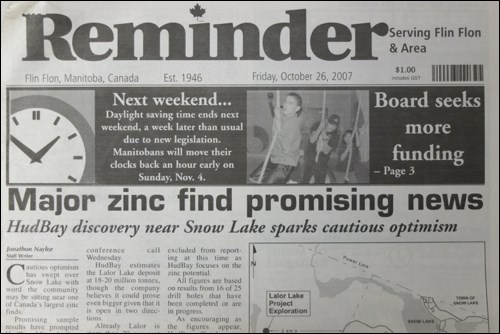

Hudbay also spent hundreds of millions of dollars to develop its Reed and Lalor mines.

Reed mine, located 120 km from Flin Flon, reached initial production in 2013 and commercial production in early 2014.

Lalor, situated 15 km outside Snow Lake, has proven to be one of the company’s most significant finds to date. The mine began ore production from its ventilation shaft in 2012 and from its main shaft in 2014.

In 2015, Hudbay purchased the former New Britannia gold mine and mill in Snow Lake. The company expressed more interest in the mill than the mine, which it did not intend to reopen.

This work was in addition to the many millions of dollars Hudbay and other companies spent on exploration in the region.

In the broader business sector, new businesses such as Lloydy’s Corner Store opened their doors.

Some existing businesses, such as Northland Ford, Twin Motors, Major Drilling and the Creighton Petro-Canada station, invested substantial dollars to upgrade their facilities.

In 2016, North of 53 Consumers Co-op announced perhaps the single largest retail investment in Flin Flon history: a $16-million to $17-million new store off of Highway 10A. The store is slated to open in the spring of 2018.

This era also marked the end of the line for a number of iconic businesses, including Johnny’s Confectionery, Freedman’s Confectionery (formerly Freedman’s Fall-in), the Hong Kong Restaurant, the Gateway Drive-in restaurant and, in Cranberry Portage, Streamer’s Hardware.

Also gone were Hudbay’s landmark South Main (between Flin Flon and Creighton) and North Main (near the company main gate) head frames, which were demolished in 2009 and 2010 respectively.

On the municipal front, the City of Flin Flon, with assistance from the provincial and federal governments, opened a new water treatment plant in 2013, ensuring residents’ drinking water met health standards.