"We were very isolated. We had no road out. Most of the town had no waterworks,” recalls Doug Evans of growing up in Flin Flon.

Hmmm. What was that like?

“For kids it was a wonderful place to live. I don’t think there’s another community that has as many fond memories as [Flin Flon does].”

Evans, now 88, grew from a child to a young man between 1937 and 1947. As the son of Mayor George Evans, who served in 1937 and 1938, he had a unique vantage point from which to observe Flin Flon.

“We were really too young to appreciate what he was doing, but it was an exciting time,” he recalls. “A lot of entertaining at our house. In those days people dressed up a lot, so the men would come in their white shirts. It was kind of funny because they would often arrive at the house in big overshoes and mukluks and so on, and then take all that off and put on their patent leather boots.”

The Evans were among the first Flin Flon families to have a phone in their home. It hung on the wall near the front door because many of their fellow residents would stop by to place calls.

Hmmm. So random people would make calls from their house?

“Nobody was random – we knew everybody,” says Evans with a smile.

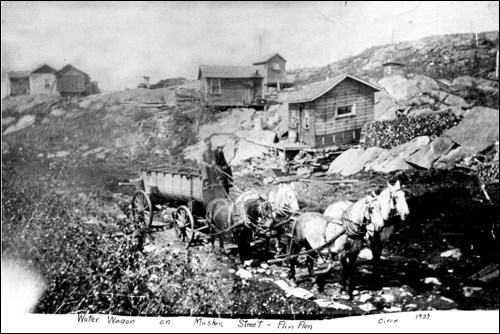

With no indoor plumbing, the Evans stored a barrel in the kitchen. It was regularly refilled by “the water wagon,” a tank first drawn by horses and later situated on a truck.

“Men would come in with two big pails of water and dump them in the barrel in the kitchen,” says Evans. “That was the drinking water, washing whatever, everything.”

Some families of the era had outdoor toilets. Others, like Evans’ family, had an indoor model. Their toilet was a pail laced with chloride lime and situated in a small room off of the kitchen.

Arriving regularly to empty the toilets was the “honey man” in his “honey wagon,” descriptions that made the job sound far more appealing than it actually was.

“Unfortunately for us, the route of the honey man came by our place about 8 in the morning [during] breakfast,” Evans says with a laugh. “And he had to march through the kitchen with his pail from the toilet [to empty it into his truck].”

Though Flin Flon was far removed from the battlefields, life this decade was dominated by the Second World War.

“We were terrified. We were losing the war,” recalls Evans, who followed the war through radio and movie newsreels. “France had fallen, Poland had fallen, Rommel had gotten almost to Cairo. Ships were getting sunk by the hundreds. It really didn’t look like we were going to win, the first two or three years.”

Evans, who several years ago founded the Flin Flon Heritage Project, notes the community played a key role in the war effort.

“We were producing…a very high percentage of the metals that the war effort needed,” he says. “There were a lot of men here went to war. There were a lot of single men at that time around…so a lot of them joined up. But the mine had to keep going. A lot of women started to work in the mine at that time…mostly in the zinc plant, in the canvas shop, rubber shop, places like that.”

Evans still remembers the day victory was declared and the war ended.

“There was an impromptu parade down Main Street. I was part of it,” he says. “I played clarinet in the Elks Band as a young person…but any band members that were around grabbed their instruments and we had a very informal parade down the street with a lot of hollering and jumping around. Later on, the town got its act together and created a proper parade.”

A rather infamous part of life in early Flin Flon was the heavy smelter pollution from HBM&S, as thick smoke spewed from the two so-called short stacks.

“It was very bad,” Evans notes. “Walking to school, if a big cloud of it came down, people were used to you knocking on the door to come in and get out of the smoke until it lightened up a bit. You didn’t do that every day of course, but once in a while. Or you got used to collecting a big ball of spit in your mouth…because the moisture would catch the smoke.”

The sulphur dioxide spewing from the stacks would also mix with water to form sulphuric acid, which could eat holes in cotton clothing.

“If you had cotton clothes hanging on the clothesline, you had to rush out and retrieve them all before the smoke got at them,” Evans says.

By the end of the decade, Flin Flon had a still-popular hockey team known as the Bombers (they were originally known simply as the Flin Flon hockey club), a bustling general hospital and a booming curling scene.

It was a decade of immense growth in the education system, with three new schools constructed and five additions added to the schools. Among the new schools was Hapnot School, now known as Hapnot Collegiate in a different location, which opened in 1938.

Media begins

With the flick of a switch, Flin Flon changed forever on November 14, 1937.

The birth of CFAR radio ushered in a new era of entertainment, information and communication for the community and the broader area.

“It probably brought the entire region closer together, no question about it,” Garry Moir, a veteran Manitoba broadcaster and journalist, previously told The Reminder.

Broadcasting in the region originated with CFAR, the brainchild of a radio-loving entrepreneur named Monty Bridgman.

“He decided that he would try to get this radio station going in Flin Flon in the 1930s, which was not a very good time because there was a Depression going on and it took them a long time to get it off the ground,” said Moir.

Bridgman and two partners promoted the idea of a Flin Flon radio station as early as 1934, but they didn’t secure a license until May 1937.

After several months of devising and testing the necessary infrastructure, CFAR hit the airwaves from a studio near the rear of the Northern Café on Main Street.

“It was so important in that there obviously had never been anything like it before,” Moir said. “Radio had been going in southern Manitoba since the early 1920s [but] the North never really had any radio until CFAR came along.”

CFAR’s early days were dominated by local content, such as Bert Wilson calling barn dances and the band Welcome Morris and His Oldtimers performing from the old Elks Hall.

More famously, CFAR became the first radio station in Canada, and most certainly the world, to broadcast in Cree.

Also during this decade, the Flin Flon Daily Reminder debuted on October 16, 1946. It was founded by the late Tom Dobson, an HBM&S employee with a passion for journalism.

The Reminder, as it later became known, competed with the community’s original newspaper, the Flin Flon Miner.

Longtime Flin Flon resident Gordon Mitchell, now deceased, once recalled how the two newspapers’ content would often mirror each other.

“Generally you expected that you’re going to see the same thing written up, only by a different person. Most often that happened,” Mitchell told The Reminder in 2006.

The Reminder became Flin Flon’s primary newspaper in February 1966 after a fire destroyed the Miner’s headquarters and the publication ceased.